Global Food Prices in 2011 Face Perilous Rise

NY TIMES

Food

prices globally are rising to dangerous levels. There is talk of a coming

crisis, like the ones that produced riots around the world in 2008 and

1974. Many of the ingredients of a disaster are present, but governments

can stop the problem before it causes too much damage. A warning sign is

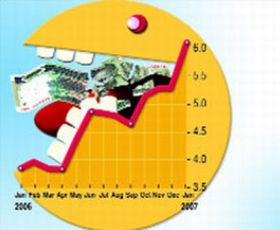

the price of traded staples like wheat, corn and rice. Prices shot up in

2010, soaring 26 percent from June to November and brushing the peaks of

2008, according to the Food Price Index kept by the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations. That hits poor countries that import

much of their food, including the Philippines, Mexico, Nigeria and Pakistan.

Food

prices globally are rising to dangerous levels. There is talk of a coming

crisis, like the ones that produced riots around the world in 2008 and

1974. Many of the ingredients of a disaster are present, but governments

can stop the problem before it causes too much damage. A warning sign is

the price of traded staples like wheat, corn and rice. Prices shot up in

2010, soaring 26 percent from June to November and brushing the peaks of

2008, according to the Food Price Index kept by the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations. That hits poor countries that import

much of their food, including the Philippines, Mexico, Nigeria and Pakistan.

High prices deprive the poor, who already spend as much as half of their income on food. The market still clears, but at a riot-inducing high price.In India, where the cost of onions has in the past led to the upending of governments, prices of the good have again skyrocketed.

For most big countries, food prices are a domestic affair. Just 12 percent

of cereals produced are traded across borders. In countries that grow

their

own, like China, Russia and India, buyers often pay prices set by the

government that have little link to global markets. Yet these nations

are

suffering, too.

China, which only really uses global markets for soybeans, is fretting

over

soaring shop prices for goods as diverse as pork and seaweed. In India,

a

fifth of the population is undernourished, according to the United

Nations.

Both countries have their own issues; for instance, in India, awful

infrastructure means a third of produce spoils before it reaches the

market.

But something is clearly making the problem worse.

It isn't shortages. True, demand for staple grains is predicted to rise

2

percent in 2011, even as production falls 4 percent. But grain reserves

run

to almost 17 percent of total use, according to Rabobank, which is

about the

level generally seen as a sensible buffer.

Nor are the main problems population trends or changing eating habits

in

developing markets. That extra demand may be making the world a bit

more

crisis-prone, but more productive, mechanized farming methods in China,

India and Africa have potential to create some slack.

The main cause looks to be too much money. Governments have effectively

printed the stuff to help their economies recover.

This has created two side effects. First, investors have bought exposure

to

commodities as an economic hedge. Second, the price of foodstuffs has

been

bid up as low interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of hoarding

them -

especially in China, where the money supply grew almost 20 percent

in 2010.

Whether those high prices turn into a crisis depends on two things.

First,

there are short-sighted policy responses. Food producers often ban

exports

when they fear shortages or price spikes are coming.

Sometimes they are right to worry. Russia's recent droughts have left

it

with a genuine wheat shortfall. And India has just banned the export

of

onions to address the latest flare-up.

But India also introduced a rice export ban in 2007 when it still had

a

sizable surplus, helping to double the world price. By 2008, more than

30

countries had some kind of controls in place. Export bans often cause

bubbles abroad; they also stop farmers from benefiting from high prices

that

would get them growing more.

The second flash point is the price of oil. That increases transport

costs

for food. But it also encourages politicians to divert grains into

biofuels,

which become competitive when oil hits $60 a barrel.

The average oil price in 2011 is forecast at $84, according to a Reuters

poll. The United States, which supplies two-thirds of the world's corn

exports, diverted huge amounts into biofuel in the run-up to the 2008

crisis, causing 70 percent of the rise in corn prices, according to

the

International Monetary Fund. That distortion was passed straight onto

the

world's poor.

Food riots in 2011 are possible, but not inevitable. Granted, the world

will

have to get used to more food scares as the population expands and

the diets

of the poor get richer. But the moment when humanity outgrows the earth

is

thankfully not yet here. Cool-headed policies can still prevent a real

crisis. JOHN FOLEY NY TIMES

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/29/business/29views.html?_r=2&src=busln

<===BACK TO THE FUTURE